A Research Paper of mine, titled “Photographing Women and Indigenous Populations in Late Nineteenth-Century Japan Through a Lens of Western Colonialism and Orientalism – Photography as a Colonial Tool,” was accepted into, and set to be published in the Second Issue of JAHMS.

Photographing Women and Indigenous Populations in Late Nineteenth-Century Japan Through a Lens of Western Colonialism and Orientalism – Photography as a Colonial Tool

Abstract

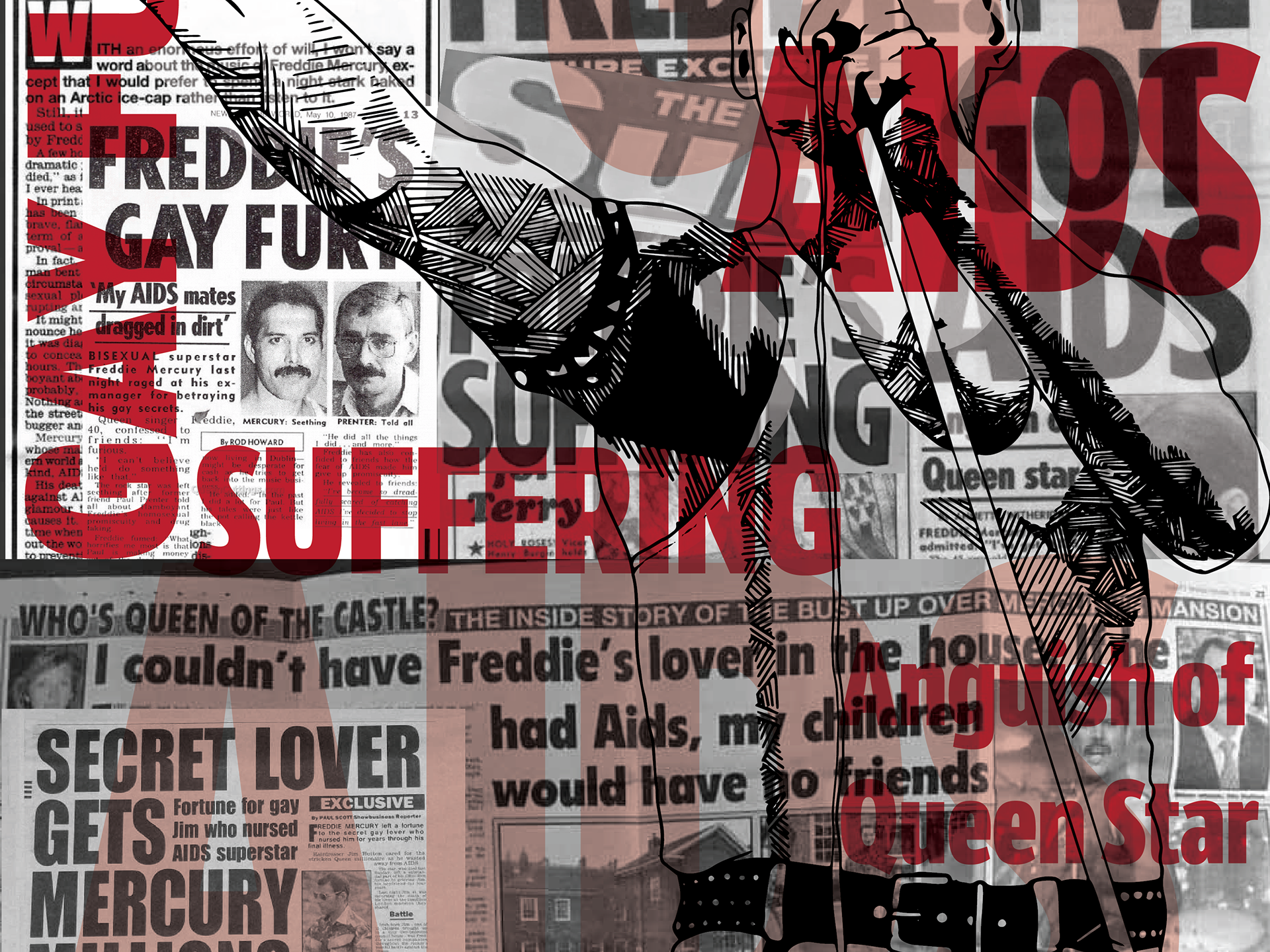

This paper works to answer the following question: how did Western beliefs and practices of Colonialism and Orientalism influence Japanese photography during the late 19th century? In addition, how did Colonialism affect photography, both specifically within Japan as well as universally, and how did it affect the way photography captured identity? Out of the photographs examined, what looks like portraits serving as an honorific way of capturing a culture, are in reality, ethnographic records [scientific records of people and cultures], or souvenirs for Western audiences (Europeans.) Colonialism, in conjunction with Orientalism, altered Japanese portraiture through the portrayals of indigenous and female identities, as well as by making photography as a whole more profit-oriented and commercialized. The identities of indigenous groups and Japanese women were either erased or altered, through the objectification, dehumanization or sexualization that emerged as consequences of Colonialism and Orientalism. Photography grew from an artform, to a visual documentation and witness of the dehumanization and marginalization of indigenous groups and women during the vast colonization during the 19th century. This new “genre” of photography emerged as a result of colonization and helped to further its progression. Moreover, the effects of Colonialism within Japan, were not isolated incidents, but rather examples of a universal abuse of photography that was especially prominent in the 19th century. Photography has been misused and abused across continents and for centuries, and such misuse is strongly evident in the 19th century, within Japan and North America (present day United States.) Figures 3 and 4, taken in North America rather than Japan, reveal the intertwined connections between European colonization in modern day United States, and its impact on Japanese Colonization techniques, especially their use of photography.

By extent, one could even argue these photographs, as they grew into exotic souvenirs for Western travelers and ways of documenting colonization, are no longer considered portraits. They do not honor identity, or humanize the individual(s) photographed, so I will avoid using the term “portraiture,” or “portraits,” which work as artistic artforms to memorialize their subjects to describe them, and instead use the word “photograph.” When the word “portrait” must be used to describe the nature of the photographs analyzed, it will be in quotations, since it is questionable whether or not these images can be labeled as portraits.

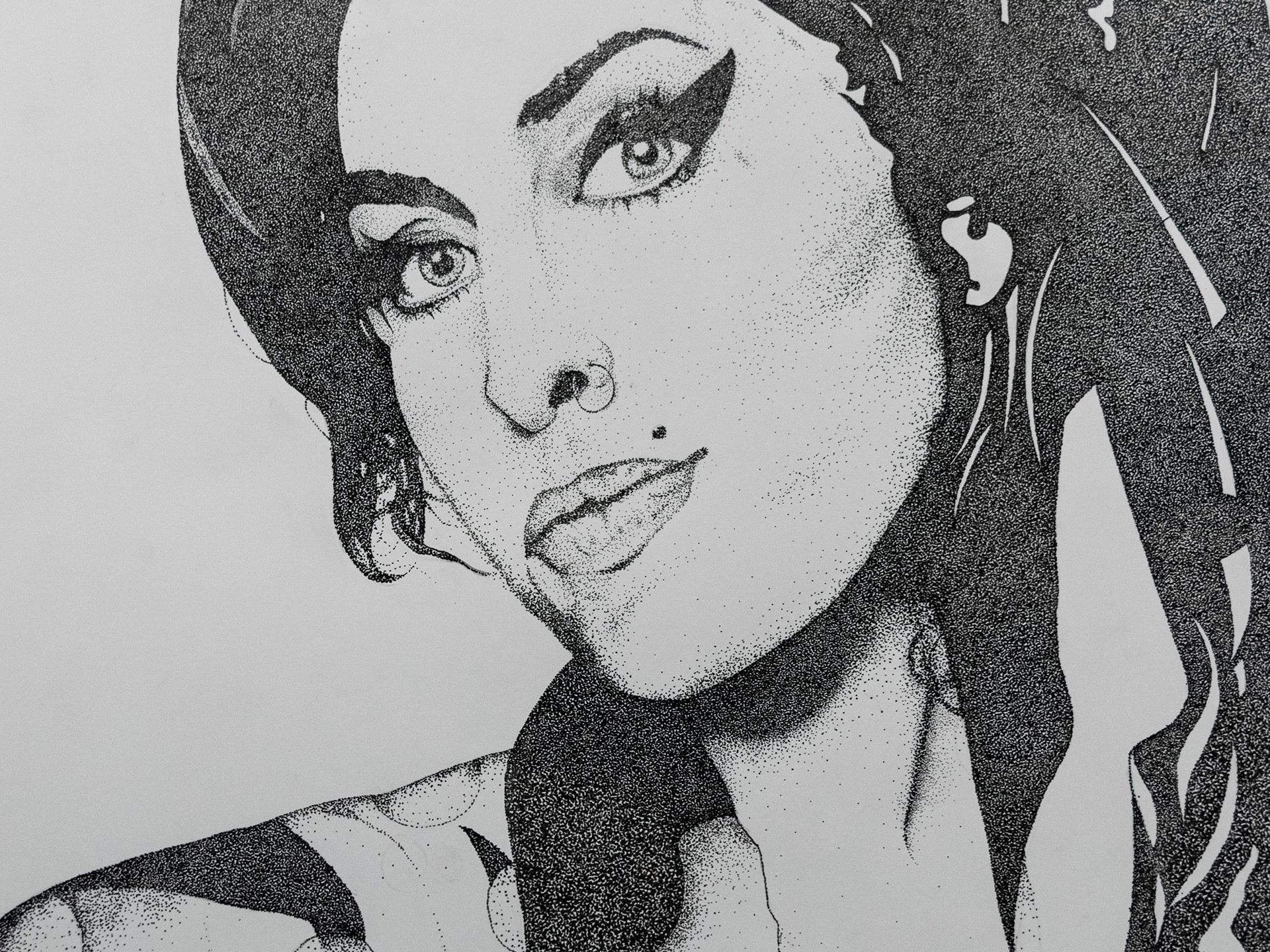

As defined by Ronald J. Horvath in “A Definition of Colonialism,” Colonialism is “a form of domination – the control by individuals or groups over the territory and/or behavior of other individuals or groups.” 1 Colonialism is most often associated with exploitation, an emphasis on economic variables, culture-change processes, and power, according to Horvath. The term Orientalism is often credited to Edward Said, a Palestinian-American professor of Literature at Colombia University, from his 1978 book “Orientalism.” Said defines Orientalism as an idea that “not only creates but also maintains… a certain will or intention to understand, in some cases to control, manipulate, even to incorporate, what is a manifestly different (or alternative and novel) world.” 2 Although not explicitly included in Said’s definition, the following analysis of Figure 2, Geisha Resting reveals that Orientalism often can have sexualized, fetishized, or misogynist undertones rooted in stereotypes of non-Western cultures. For clarification, when analyzing Figures 1 and 2, which were taken in Japan or the island of Hokkaidō, the term “West” or “Western” is used when referring to Europe. When analyzing Figures 3 and 4 from North America, “Europe” will be used. For reference, these words are one in the same, and differ only based on the geographical location/common terminology of the origin country for the photograph in question.

Many credit “Hokkaidō Photography” as the beginning of documentary photography in Japan. Hokkaidō, a northern island once native to the indigenous Ainu population, was colonized and incorporated into Japan in 1868. Not unlike previous scholarship, this paper dives into the photography that emerged from the island of Hokkaidō. However, it analyzes how Hokkaidō photography and the colonial relationships it captured visually, were byproducts of Western practices and revealed the correlation between colonialism and the erasure of indigenous identity. This will be revealed primarily through an analysis of Tamoto Kenzô’s (1832-1912) double “portrait” Ainu Women (c. 1890s), (Fig. 1.) Around the same time, Western Orientalism impacted the way Japanese photographers photographed women; new photographs were more sexual relied heavily on stereotypes to appeal to their new Western audiences with the opening of Japan’s borders. Thus, this paper will put Kenzô’s double “portrait” in conversation with Kusakabe Kimbei’s (1841-1934) double “portrait” Geisha Resting (c. 1885) (Fig. 2.) Kenzô’s photograph will also be analyzed alongside two photographs from North America; Chiricahua Apaches Four Months After Arriving at Carlisle (19th century) (Fig.3) and The Vanishing Race, Edward Curtis (1868-1952) (Fig.4,) to reveal how the evolvement of Japanese photography due to Western/European influence, was not a singular incident, but rather just one example of how European colonization across the globe, changed the way “portrait” photography was used. By examining both photographs in relation to Western influences, this paper reveals how images that are seemingly portraits, or photographs of people, can work beyond the honorific genre, in this case creating an ethnographic specimen or an “exotic” souvenir, respectively, and upholding ideologies of Colonialism and Orientalism in Japan and around the world. Both images, Ainu Women and Geisha Resting, also display how photography has the potential to be used to create what we can interpret as “art,” as well as records, commercial products, etc. The images also show how identity, can be challenged, or destroyed because of concepts such as Colonialism and Orientalism, which place certain groups (i.e., Indigenous groups or women,) lower on a social scale. Photography was used, not as an art form, but as a means of capturing and perpetuating social hierarchies by invalidating the identities of women and indigenous groups. In Japan and the island of Hokkaidō, photography served a visual record of the twisting of Japanese (Geisha) women to please Western audiences, as well as the erasure of the indigenous Ainu population.